About the exhibition

At Bill’s funeral, his brother Thomas got up and spoke about how Bill had looked out for him, taken him to parties and shown him how to draw, just as their father had taught Bill. Don’t just draw a tree and a boy and a dog, Bill would say. Draw the boy falling out of a tree and the dog having a poo. Bill was a sharp observer and he paid attention to the theatre of the everyday. He was always open to being amused by even the most mundane skit, filing it away for later. A small encounter was often relayed by Bill with the gravity of Breaking News, like dispatches received from the world outside, just in.

At Bill’s funeral, his brother Thomas got up and spoke about how Bill had looked out for him, taken him to parties and shown him how to draw, just as their father had taught Bill. Don’t just draw a tree and a boy and a dog, Bill would say. Draw the boy falling out of a tree and the dog having a poo. Bill was a sharp observer and he paid attention to the theatre of the everyday. He was always open to being amused by even the most mundane skit, filing it away for later. A small encounter was often relayed by Bill with the gravity of Breaking News, like dispatches received from the world outside, just in. Standing in our driveway he would turn to our resident song thrush Hector and say, “what a fine spotty vest you’re wearing,” appreciating the performance, his petite flamboyance. Then looking at my parked car he would hiss, “Pulssaaar” just to hear it sizzle about on his tongue.

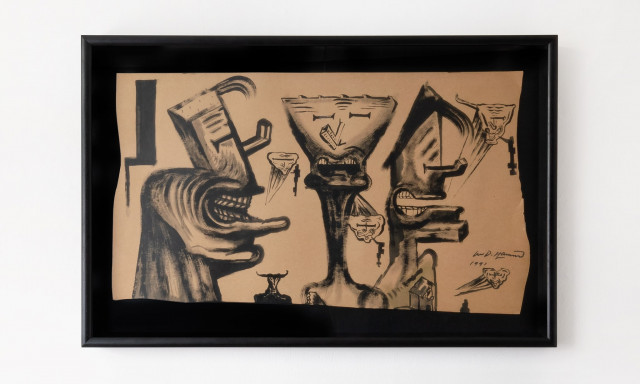

Everything was at his disposal: transistor radios, televisions, cacti, birdcages, the entrapment of the human mind. The works in this exhibition, which come from the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s, take suburban life as a stage for exploding possibilities. These cramped interiors and sketches like snatches of dreams, inject humour into the banality and anxiety of life at the time.

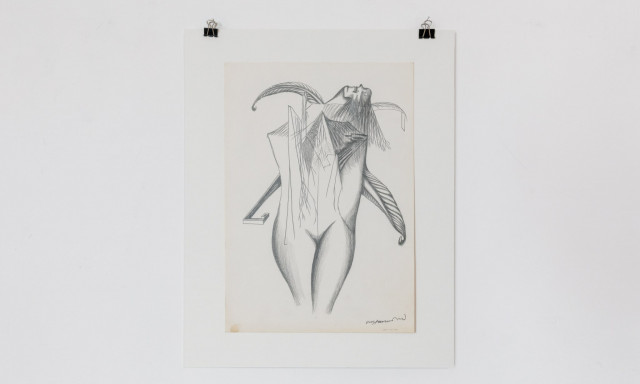

Despite bringing together seemingly disparate things, they are fastened together by his compositional brilliance. With tilted floors divided by the dusty grandiosity of red velvet curtains, strong diagonals and extreme perspectives, he holds the accumulation of subject matter together, at ransom even. His draughtsmanship is loose and astute all at once. Drawing from advertising and pop culture, Japanese woodcuts and renaissance painting, Hieronymus Bosch and Robert Crumb, his sampling is non-hierarchical but fit for purpose. His props came from advertising catalogues or World of Interiors, his set might be a line of poplars snatched from a de Chirico painting, and the drapes are often, as they say, the stylists' own. Admire the line of a bullish neck or the Egyptian style depiction of strange and straining bodies. He draws our attention to a bulging bicep or a jeering mouth, then twists and yanks limbs in the opposite direction. Legs sprint from beneath a stretched and sinewy body, parallel to the floorboards like a cartoon.

These works sit somewhere between what we know and don’t know, between what is familiar and alarming. In Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright no one rushes to extinguish the birdcage licked with flames. Mysteriously the sprinkler is also ablaze, while a nuclear explosion goes unnoticed. It’s inexplicable why the loose-tongued figure with a spray can has, what looks like, a scythe for an arm and wears such frilly footwear. But we recognise these gestures and features; perhaps we have also recently glanced at a woman in a red dress only to find she has a prehistoric forehead. Or spent a languid afternoon staring at a patterned concrete block wall, watching the forms and shadows swap places.

And yet in all the chaos, there is this stillness that is so distinctly Hammond, where the scene seems to dangle in wait. For a drink, a cigarette, or the moment a hand clenches to a fist. Later, Bill’s watchful birds will wait for Buller, performative in their solemnity. But here time seems to compress in agitated anticipation. The trope of the park bench – used in films for the overt rendezvous or the unlikely meaningful encounter – sits empty, waiting for the story to unfold. He stops short of being judgemental or disapproving though. His stage is one of community theatre, where there is a place for everyone, all talents considered. Where the grotesque and the beautiful can have a drink together under an atomic sky.

Breaking News from the Home Theatre by Holly Best

Bill Hammond, 1984

Acrylic on un-stretched canvas, 1920 x 1860 mm

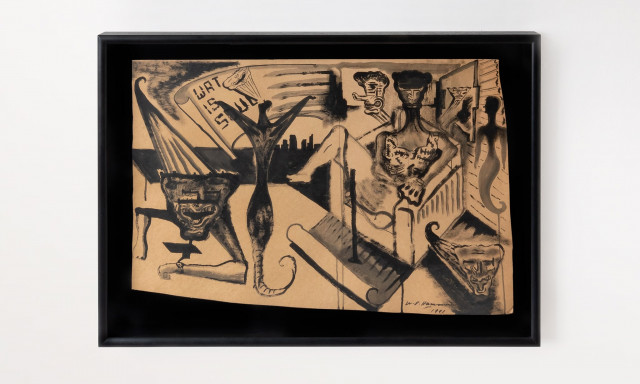

Bill Hammond

Ink on paper, 570 x 720 mm

Bill Hammond, 1991

Ink on paper, 770 x 1080 mm (framed)

Bill Hammond, 1991

Ink on paper, 770 x 1080 mm (framed)

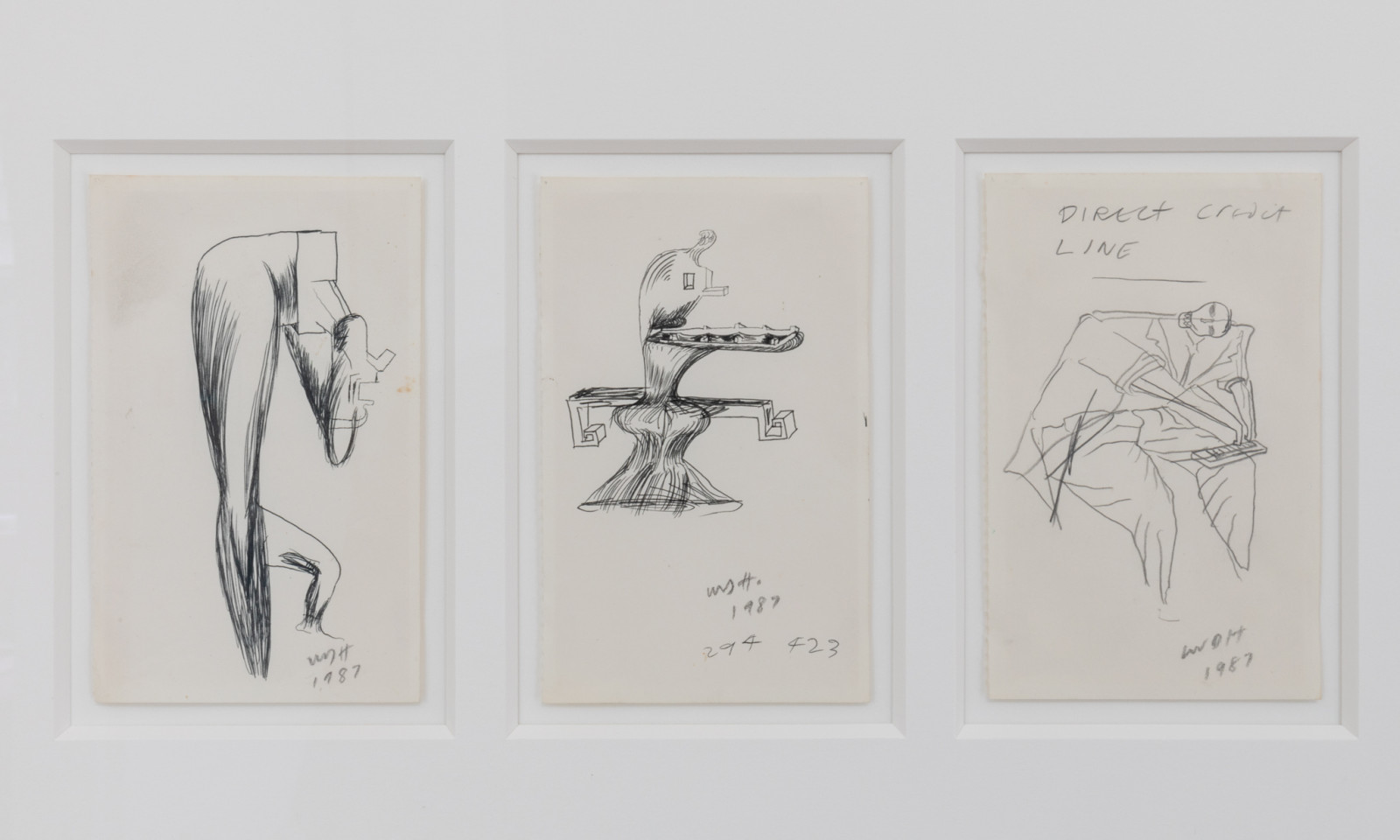

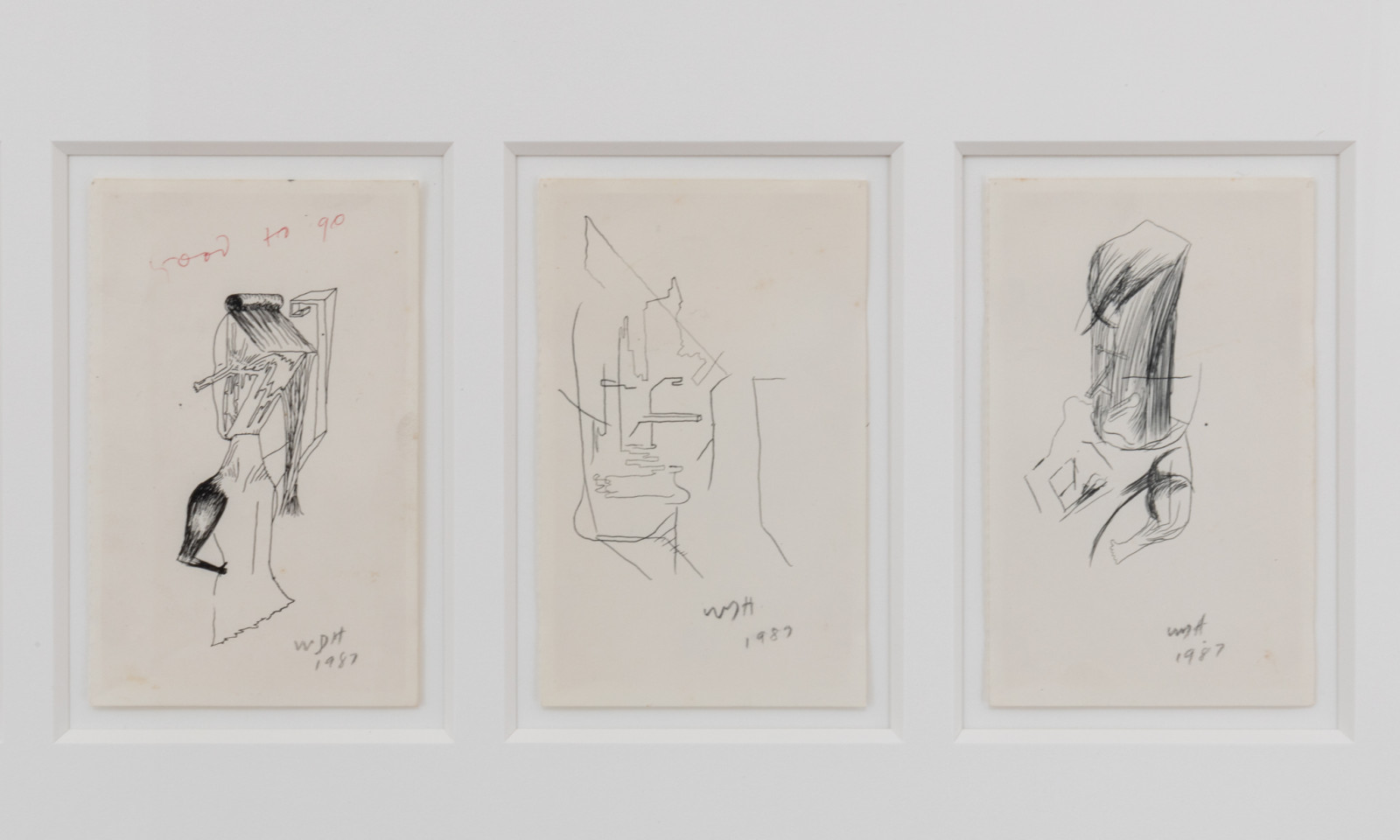

Bill Hammond, 1987

Graphite and pen on paper, 350 x 1050 mm (framed)

Bill Hammond, 1978

Ink on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

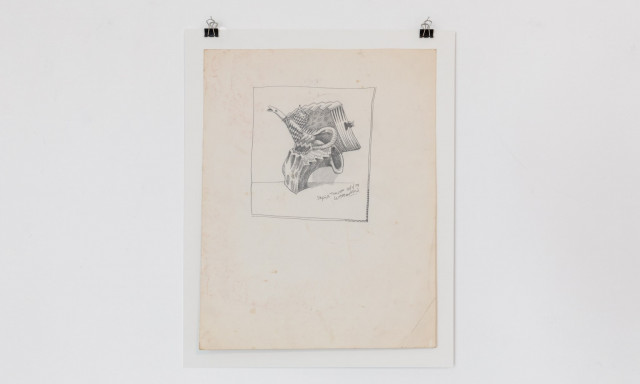

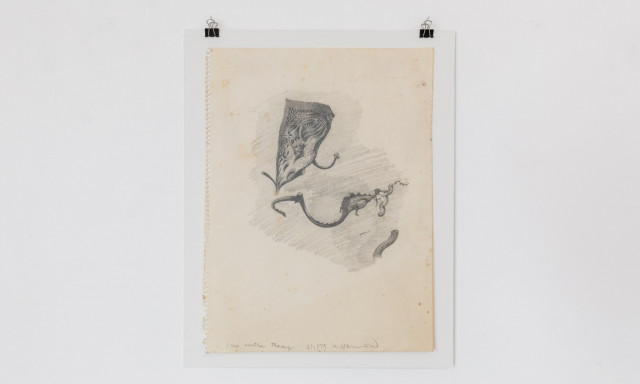

Bill Hammond, 1979

Graphite on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

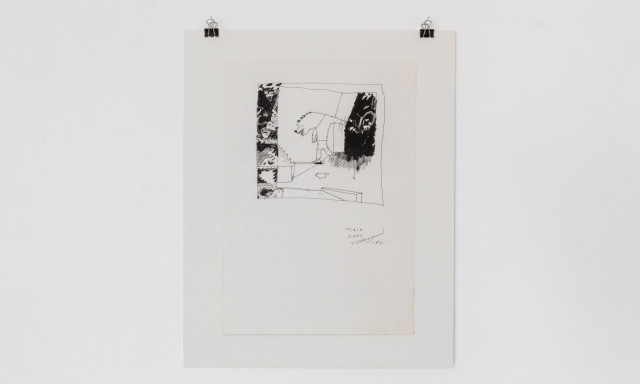

Bill Hammond, 1981

Pen and ink on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

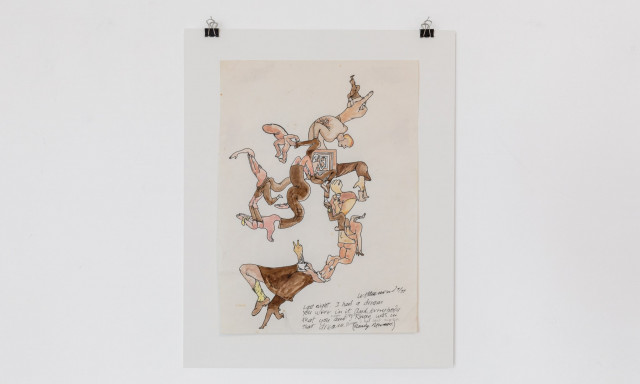

Bill Hammond, 1977

Pen and paint on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

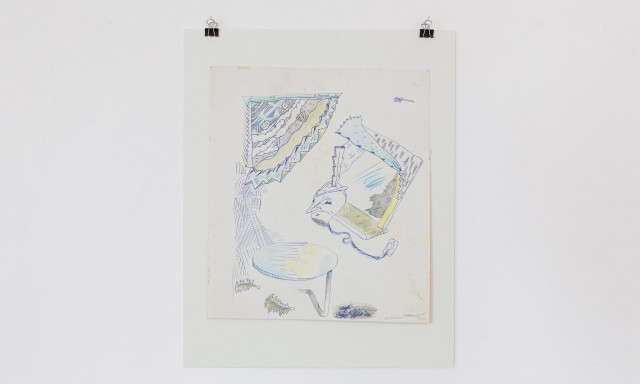

Bill Hammond, 1980

Pen and coloured graphite on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

Bill Hammond, 1989

Graphite on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

Bill Hammond

Ink and paint on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

Bill Hammond

370 x 300 mm (mounted), 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

Bill Hammond

370 x 300 mm (mounted), 370 x 300 mm (mounted)

Bill Hammond, 1980

Ink on paper, 370 x 300 mm (mounted)